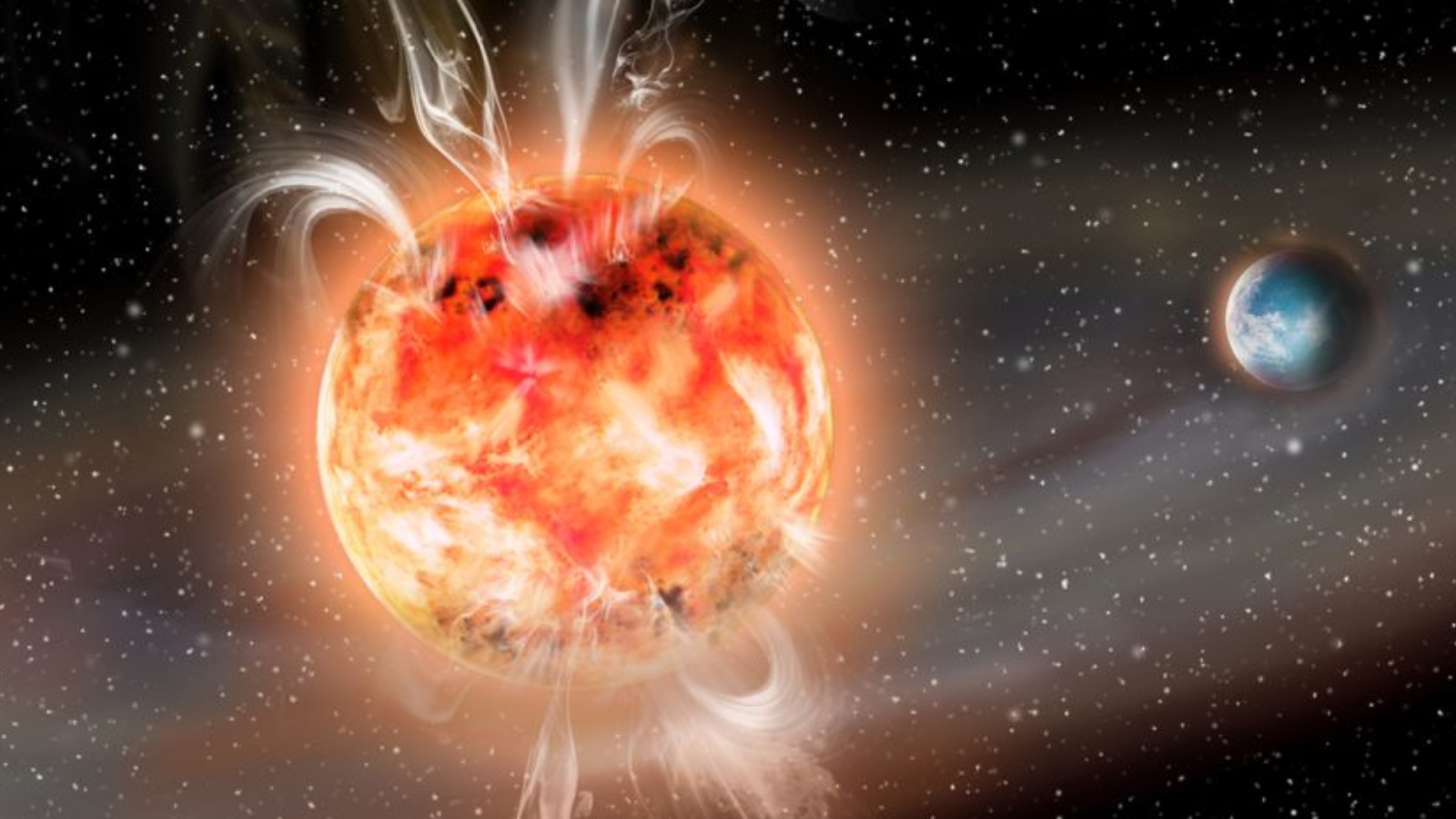

High-energy, powerful, and violent stellar explosions called “superflares” have been found to erupt from stars like the sun roughly once every 100 years, making these blasts far more common than scientists had thought.

Solar flares, eruptions of high-energy radiation, can have serious effects on Earth, with the potential to impact communication systems and power infrastructure.

However, solar flares are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of outbursts of energy that stars can emit. A more extreme phenomenon is the “superflare,” an explosion that can be tens of thousands of times more powerful than the “typical” solar flare.

One of the most violent solar storms on record was the Carrington event of 1859. During this storm, telegraph networks across Europe and North America collapsed. Worryingly, the Carrington event — as extreme as it was — released just 1% of the energy that could be emitted during a superflare.

Related: The worst solar storms in history

While astronomers had been aware of the existence of these worryingly powerful flares from the sun, such outbursts had, until now, appeared to be rare.

“Superflares on stars similar to our sun occur once per century. This is 40 to 50 times more frequent than previously thought,” study team member Valeriy Vasilyev, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, told Space.com. “If our sample of sun-like stars is representative of the sun’s behavior, our star is substantially more likely to produce a superflare than was previously thought.

“Everything about this discovery was surprising.”

The team’s research was published on Thursday (Dec. 12) in the journal Science.

Why turn to the stars to study the sun?

This year, the sun has been particularly turbulent, blasting Earth with usually strong solar storms and ramping up auroral displays as a reminder of how violent our star can be. While scientists have been able to study this behavior and collect invaluable data, this represents the sun’s behavior over a tiny fraction of its 4.6 billion-year life so far.

There’s a record of more long-term behavior of the sun and its outbursts sealed within prehistoric trees and in glacial ice that is thousands of years old. However, these indirect methods aren’t capable of showing us how frequently the sun has thrown a major tantrum and launched a superflare.

Searching for this info, Vasilyev and colleagues turned to a sample of thousands of other stars, which they determined to be sun-like in terms of their stellar class and their behavior.

“We cannot observe the sun over thousands of years,” team member Sami Solanki, director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, said in a statement. “Instead, however, we can monitor the behavior of thousands of stars very similar to the sun over short periods of time. This helps us to estimate how frequently superflares occur.”

Vasilyev explained that the team took into account an improved understanding of stars with sun-like behavior or “near-solar variability” delivered by recent research. They then turned to data collected by NASA’s Kepler space telescope between 2009 and 2013. This amounts to the equivalent of 220,000 years of stellar activity.

Stars that appeared to be particularly “close relatives” of the sun were selected from this data set.

“Using this improved understanding, we selected a new solar-stellar comparison sample that is much larger and more representative of the sun than previous samples,” Vasilyev continued. “We also developed a new method to detect flares and localize them with subpixel resolution, taking into account instrumental effects.”

The team observed 2,889 superflares on 2,527 of the 56,450 observed stars. This equates to, on average, one sun-like star producing one superflare every 100 or so years.

According to Vasilyev, the team’s results also indicated for the first time that the frequency of solar and stellar flares is consistent with each other. This suggests that the same mechanism generates flares on the sun and on sun-like stars.

A warning to Earth

Solar flares are often accompanied by massive ejections of plasma called coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. When large amounts of high-energy particles from CMEs hit Earth, they generate radioactive materials that are sealed in the geological record.

This has allowed scientists to identify at least five extreme solar particle superflare events from the sun during Earth’s history. Three of these occurred in the last 12,000 years, with the most violent appearing to have lashed our planet in 775 A.D.

However, it isn’t completely clear how often superflares are associated with CMEs. This means that superflares from the sun may not always make their mark in Earth’s geological record and may, therefore, have been underestimated. It also means that the effects of superflares on Earth aren’t completely predictable.

“The effect of superflares on Earth? That’s a good question. There are various aspects to consider,” Vasilyev said. “What is the potential impact on technological systems? How do these events affect the biosphere? There are a lot of interesting questions to answer.”

Related: Space weather: What is it and how is it predicted?

Research produced in 2018 by a separate team of scientists suggested that a superflare from the sun could have catastrophic effects on Earth’s atmosphere and, thus, life.

However, in 2021, another research team found that superflares tend to erupt from closer to the poles of stars, meaning that if the sun erupted with such a flare, there is a good chance it would miss Earth.

“I hope this study will motivate other researchers to investigate the potential impacts of such extreme space weather events in greater detail,” Vasilyev continued.

While the potential impact of a superflare event on Earth remains somewhat unclear, what is evident from this research is the need for caution.

“The new data are a stark reminder that even the most extreme solar events are part of the sun’s natural repertoire,” said team member Natalie Krivova, also from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

The team will now continue their research into superflares from other stars and the potential effects of such an event closer to home.

“There are several directions we are pursuing,” Vasilyev said. “For instance, we are investigating the impact of such events on the Earth’s atmosphere and technological systems, understanding the connection between superflares and extreme solar particle events, and determining the conditions necessary to produce such superflares.”