- Uranus’ moon Ariel might have a subsurface ocean, a study found last year. The ocean could be ancient or it could still exist today.

- A new study of unusual grooves on Ariel suggests that carbon materials on the moon’s surface originate from deep below.

- The carbon could come from the subsurface ocean, although scientists haven’t proven a link yet.

Uranus’ moon Ariel is groovy

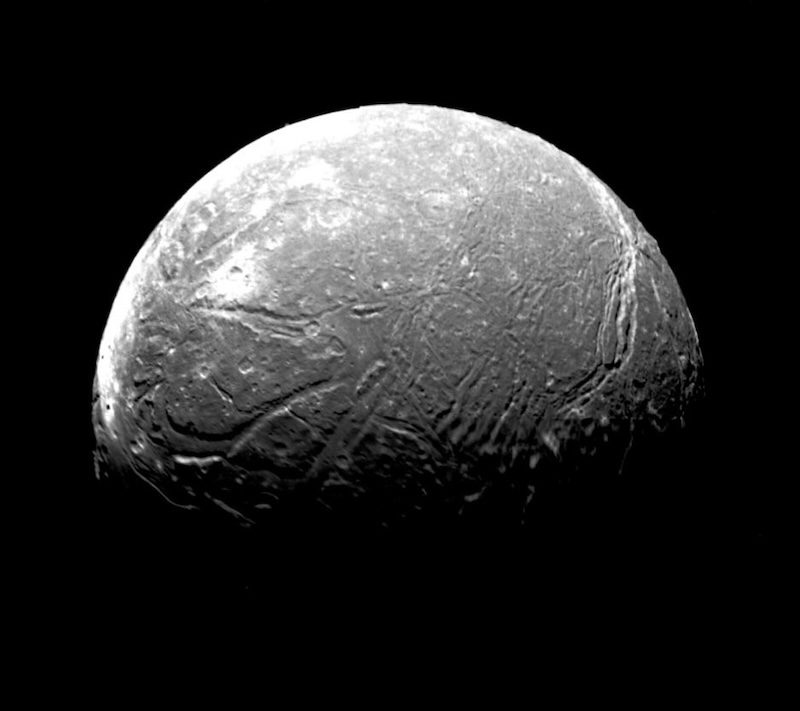

The hidden oceans on some moons of Jupiter and Saturn – such as Europa, Enceladus and others – are well-known. Then last year, scientists using NASA’s Webb Space Telescope found evidence for a possible subsurface ocean on Uranus’ moon Ariel as well. Now, a new study from researchers at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, adds to the earlier findings. The researchers said on February 3, 2025, that carbon molecules on the surface, including carbon dioxide ice, might be coming up through trench-like grooves in Ariel’s canyons. The carbon might have originated from a subsurface ocean.

The research team published their peer-reviewed findings in The Planetary Science Journal on February 3, 2025.

Carbon from deep grooves on Uranus’ moon Ariel?

Ariel has carbon dioxide ice and other carbon deposits on its surface. How did they get there? The study last year suggested they originated from within the moon itself instead of external sources. They might even be from a subsurface ocean, similar to ones on other icy moons in the outer solar system.

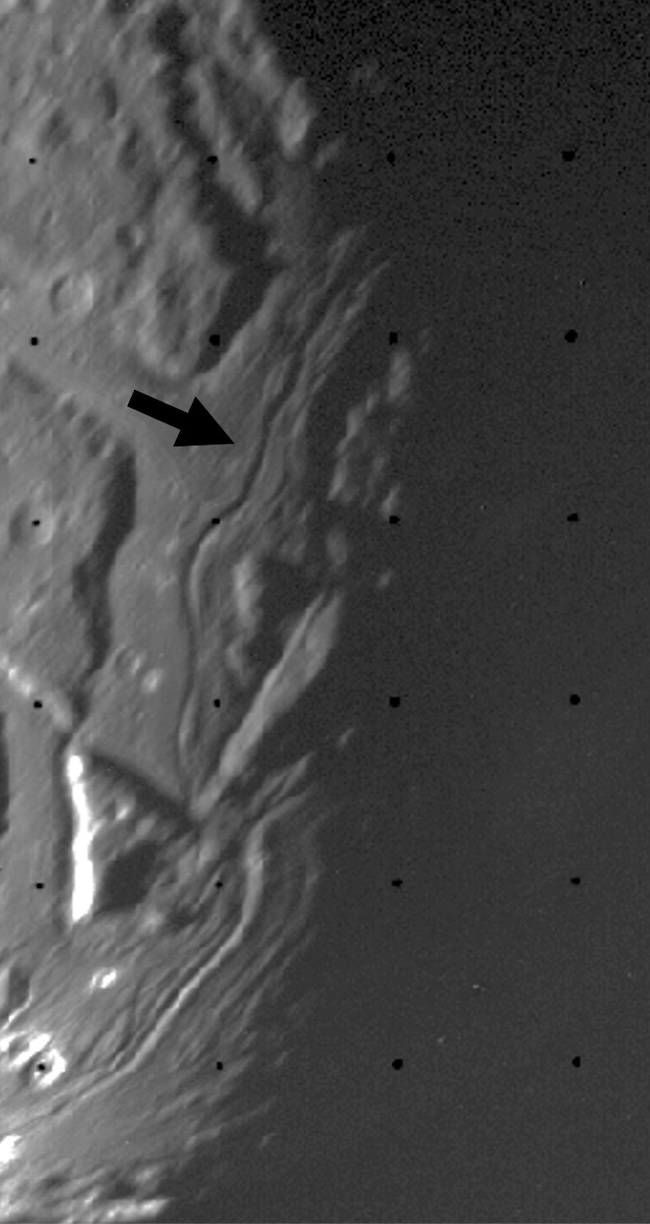

Now, the new study from Johns Hopkins shows how those materials might reach the surface. The answer might be what scientists call medial grooves. Those are trenches within Ariel’s larger canyons. Chloe Beddingfield, lead author of the new study at Johns Hopkins, said:

If we’re right, these medial grooves are probably the best candidates for sourcing those carbon oxide deposits and uncovering more details about the moon’s interior. No other surface features show evidence of facilitating the movement of materials from inside Ariel, making this finding particularly exciting.

New research from Johns Hopkins APL suggests grooves on Uranus’ moon Ariel may act as spreading centers, transporting materials between its interior and surface, similar to tectonic and volcanic activity on Earth. jhuapl.link/505

— Johns Hopkins APL (@jhuapl.bsky.social) 2025-02-03T20:32:00.274Z

Earth-like spreading centers

The researchers said the grooves are likely what scientists call spreading centers. On Earth, they are the linear boundary between two diverging lithospheric plates – regions of Earth’s crust and upper mantle that are fractured into plates – on the ocean floor. As they move apart, molten rock wells up to fill the gap. It solidifies, creating new oceanic crust.

A similar process might be occurring on Ariel. Heat from Ariel’s interior could cause carbon-rich material to move upward, splitting the surface and creating the grooves.

The researchers also considered volcanic conduits or fissures to explain the grooves. But after studying old images from NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft, spreading centers became the most likely explanation. Voyager 2 passed by Uranus and its moons in January 1986. It is still the only mission to do so.

The images provided important clues. For example, the canyon walls flanking the trenches fit together like puzzle pieces when their central floors were digitally removed. In addition, the canyon floors displayed regularly spaced ridges in some locations. This was also consistent with a series of material depositions.

Does Ariel have an ocean?

The findings strongly suggest that the carbon on Ariel’s surface came from below. But is it from an ocean? As the study last year demonstrated, there is evidence suggesting the existence of an ocean below the icy crust. Scientists know Ariel and some other Uranian moons have had multiple periods of strong geological activity. Tidal forces likely drove that activity. This can cause cycles of heating, melting and freezing inside those moons. So Ariel likely had some kind of ocean and it might still be liquid today.

The grooves and a possible ocean could help explain how short-lived carbon oxides are able to remain present on Ariel’s surface. As co-author Tom Nordheim at Johns Hopkins explained:

These new results suggest a possible mechanism for emplacing fresh material and short-lived compounds, including carbon monoxide and perhaps ammonia-bearing species on the surface.

Beddingfield added:

It’s a fascinating situation, how this cycle affects these moons, their evolution and their characteristics.

Still a lot of unknowns

Scientists haven’t proven the link between the trenches and a possible ocean quite yet, however. Beddingfield said:

The size of Ariel’s possible ocean and its depth beneath the surface can only be estimated, but it may be too isolated to interact with spreading centers. There’s just a lot we don’t know. And while carbon oxide ices are present on Ariel’s surface, it’s still unclear whether they’re associated with the grooves because Voyager 2 didn’t have instruments that could map the distribution of ices.

Scientists say that another moon of Uranus, Miranda, also likely had an ocean. And that ocean might still exist today as well.

New mission to Uranus needed

As of now, the Voyager 2 images are still the best we have. A new mission – such as the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) mission – will be necessary to further explore Uranus and its moons. Richard Cartwright at Johns Hopkins, who led last year’s study, said:

We need an orbiter that can make close passes of Ariel, map its medial grooves in detail, and analyze their spectral signatures for components like carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. If carbon-bearing molecules are concentrated along these grooves, then it would strongly support the idea that they’re windows into Ariel’s interior.

And as the paper noted:

The medial grooves are some of the youngest geologic features observed on Ariel, and close flybys of these features by a future Uranus orbiter are imperative to gain insight into recent geologic events and the geologic and geochemical properties of this candidate ocean world.

Bottom line: Deep trenches are the likely source of carbon on the surface of Uranus’ moon Ariel and might be connected to a subsurface ocean, a new study suggests.

Source: Ariel’s Medial Grooves: Spreading Centers on a Candidate Ocean World

Via Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

Read more: Does Uranus’ moon Ariel have a hidden ocean?

Read more: Evidence for ocean on Uranus moon Miranda is a surprise

Source link

Read More

Visit Our Site

Read our previous article: Europa Clipper Tests its Star Tracker Navigation System

gz07kt