This image shows the constellation Ursa Major the Great Bear. The seven brightest stars (at upper left) are the Big Dipper. Credit: Tony Hallas

Although it’s visible all year round from mid- and high-northern latitudes, now is a great time of the year for newcomers to stargazing to look for and find the famous star pattern known as the Big Dipper or the Plough.

Many people grow up believing the Big Dipper is a constellation, but it’s not. It’s an asterism — a small, eye-catching, connect-the-dots pattern made of stars lying either within a single constellation or in neighboring constellations. In the case of the Big Dipper, it’s part of the constellation Ursa Major the Great Bear.

While the Big Dipper is visible year round from many places, its orientation in the sky changes through the course of the year as Earth whirls around the Sun, and through individual nights too, as Earth spins on its axis. This means that sometimes it looks like a big starry question mark in the sky, and other times it looks like an upside-down fish hook.

As darkness falls on these increasingly-chilly late fall evenings, the Big Dipper actually looks like a dipper, or a ladle, resting across the northern horizon. Its stars are bright enough so they’re visible as soon as the first stars begin to appear, making it perfect for people who have never seen it before to look for it.

However, the Big Dipper isn’t just an attractive pattern of stars to look at on a clear night. It can be used to help locate many fascinating stars, constellations, and objects of interest positioned around it in the night sky. But before we go on a star-hopping tour from the Big Dipper, let’s take a look at the story behind the Dipper itself and meet the seven stars that we join to draw it in our mind’s eye.

Big Dipper sky lore

Because the Big Dipper is visible from many countries, it should come as no surprise that there are many tales about it. For example, there are several fascinating Native American stories about the Dipper. To the Blackfoot people, the Big Dipper was a woman who was transformed into a bear and chased her brothers into the sky, where all of them became the stars of the Big Dipper.

To the Micmac and Iroquois tribes, the Big Dipper is a bear being pursued across the heavens by seven hunters. As autumn approaches, three of the hunters tire and fall below the horizon, leaving the remaining four to chase down the bear. When it is eventually killed, its blood turns the leaves red in the fall and the bear’s skeleton remains in the sky during winter. A new bear emerges in the spring, restarting the hunt.

In China, The Big Dipper is associated with many different deities and myths. One, Doumu, is known as the Mother of the Great Chariot. She is believed to have control over the stars and is often depicted on charts with the Big Dipper.

Stargazers in many Western lands have always seen the Big Dipper as part of the Great Bear, Ursa Major. The Dipper’s curved handle represents the bear’s tail, which is rather odd because real bears don’t actually have long tails. Greek myths, however, explain this by suggesting the bear was hurled into the sky by its tail, which stretched as Zeus swung it around over his head before releasing it.

And in the United Kingdom and Ireland, the Big Dipper is not associated with a bear at all. Instead, it is known as the Plough, due to its resemblance to a traditional farming plough (or plow, in American English), pulled across fields by a horse.

The Big Dipper’s stars

With an apparent magnitude of 1.79, Dubhe (Alpha [α] Ursae Majoris) is the second-brightest star in Ursa Major and the 33rd brightest star in the night sky. It is a spectroscopic binary and lies approximately 123 light-years from Earth. It is one of the best known stars in the sky because, along with Merak (Beta [β] UMa), it’s one of the “pointer stars” that skygazers use to locate Polaris, the North Star.

Shining at magnitude 2.37, 79.7 light-years distant Merak is the fifth-brightest star in the Dipper and the second of the Pointers.

Megrez (Delta [δ] UMa) is the dimmest of the Dipper’s seven stars, with an apparent magnitude of 3.3. A spectral class A3 star, it has a surface temperature of approximately 9,500 K, giving it a white or blue-white color. It lies about 80 light-years from Earth.

Phecda (Gamma [γ] UMa) is one of the stars that form the Dipper’s bowl. Its magnitude of 2.44 makes it the sixth-brightest star in Ursa Major. It lies approximately 83 light-years from Earth. Phecda spins rapidly, around 110 miles (178 kilometers) per second, which causes it to have an oblate shape.

Alioth (Epsilon [ε] UMa) is closest of the Dipper’s handle stars to its bowl. It is the brightest star in the constellation. Its apparent magnitude of 1.77 makes it the 31st brightest star in the night sky.

Mizar (Zeta [ζ] UMa) lies in the center of the Dipper’s curved handle. It has an apparent magnitude of 2.04, making it one of the brighter stars in the constellation. Mizar is a famous naked-eye double star, perhaps one of the most famous in the sky. With its twin, Alcor (80 UMa), it is often considered a test of good eyesight. In fact, Mizar itself is a quadruple star system consisting of two pairs of binary stars.

Alkaid (Eta [η] UMa) marks the end of the Dipper’s handle. With an apparent magnitude of 1.86 it is the third-brightest star in Ursa Major. It lies approximately 100 light-years from us. Like Phecda, Alkaid is a fast spinner, rotating with an equator-bulging velocity of around 93 miles (150 km) per second.

Star-hopping from the Big Dipper

Amateur astronomy can seem like a daunting hobby at first, but every astronomer you see gazing into the eyepiece of a high-tech, high-powered, bank account-busting telescope started out as an a beginner who knew nothing. The way people begin to learn the night sky isn’t by using complicated charts or maps, but by star-hopping across the sky, drawing imaginary lines between pairs or groups of stars and extending them to point the way to other objects.

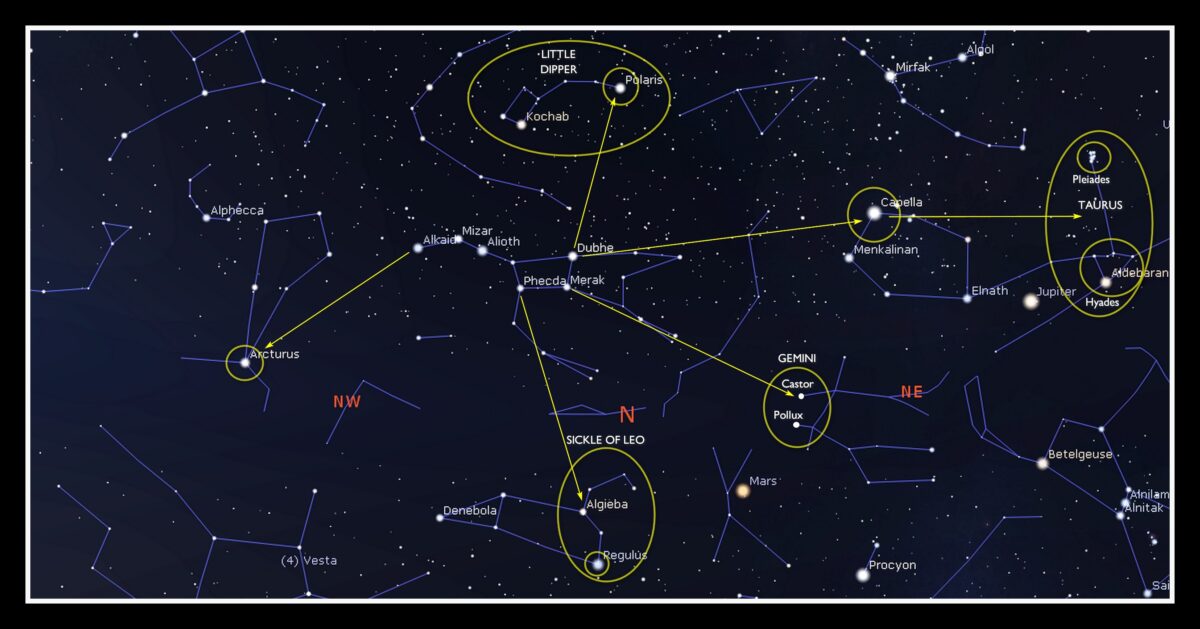

Here are six objects you can find by star-hopping from the Big Dipper. You won’t be able to see them all on one night because, depending on the time of night and your location, some will be beneath the horizon at times. But they’re worth waiting for.

- Drawing a line between Dubhe and Merak, the appropriately nicknamed Pointers, and extending it away from the bowl’s opening will lead you to Polaris, the famous North Star. Polaris is the brightest star in Ursa Minor the Little Bear, which contains the asterism the Little Dipper.

- There’s a saying in astronomy: “Follow the arc to Arcturus and speed (or spike) to Spica.” The arc in question is the curved handle of the Big Dipper. If you extend this curved line, you’ll come to Arcturus, the brightest star in Boötes the Herdsman. Arcturus is the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere (note: this is not the same thing as the Northern Hemisphere), and the fourth brightest in the whole sky. Then, if you cast your gaze in a straight line from Arcturus in the direction you were last curving, it will lead you to Spica, Virgo the Maiden’s brightest star.

- If you poke a hole in the Dipper’s bowl and let all the water run out, you’ll come to Leo the Lion. You’ll first see it as a backward question mark. This is an asterism known as the Sickle, the sharp-bladed cutting instrument used by farmers harvesting crops. The Sickle is the front of Leo and its bottom star is Regulus, the brightest in the Lion. To find the rest of him, look to the east for a triangle of stars whose brightest star is Denebola, a name that means “the tail of the lion.”

- Draw a line between Megrez in one corner of the Dipper’s bowl and Merak in the opposite corner, and extend it away from the Dipper and you will be taken to a close pair of stars. These are Castor and Pollux, the brightest stars in the constellation Gemini the Twins.

- Going back to Megrez, draw a line between it and Dubhe and extend it until you come to a bright, gold-hued star. This is Capella, the brightest star in Auriga the Charioteer, and the sixth brightest star in the sky.

- Having found Capella, extend that line from Megrez and Dubhe farther, almost as far away again, and you’ll come to two of the most famous star clusters in the sky, both in the constellation Taurus the Bull. The most obvious and smaller of the two is the Pleiades, aka the Seven Sisters or M45, which looks like a knot of silvery-blue stars obvious to the naked eye. Beneath the Pleiades is a larger, fainter cluster, a sideways V of stars called the Hyades. The bright, ruddy star at one tip of the V is Aldebaran, the Bull’s brightest sun.

As you can see, there’s a lot more to the Big Dipper than meets the eye. It’s not just a comfortingly familiar pattern of stars, it’s a treasure trove of fascinating cultural stories and a signpost to some of the most famous objects in the night sky.

Read our previous article: 1st monster black hole ever pictured erupts with surprise gamma-ray explosion