The term quasar comes from quasi-stellar objects, a name that reflected our uncertainty about their nature. The first quasars were discovered solely because of their radio emissions, with no corresponding visual objects. This is surprising since quasars blaze with the light of trillions of stars.

In recent observations, the Hubble examined a historical quasar named 3C 273, the first quasar to be linked with a visual object.

Maarten Schmidt was the California Institute of Technology astronomer who first connected the radio emissions from 3C 273 with a visual object back in 1963. At the time, it looked just like a star through the powerful telescopes available, though its light was red-shifted. Schmidt’s discovery showed us the true nature of these extraordinary objects, and now we know of about one million quasars.

A quasar is an extremely luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN) powered by a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at the center of a galaxy. Accretion disks of gas form around SMBHs, and the swirling gas heats up and releases electromagnetic energy. Only a small percentage of galaxies have quasars and their luminosities can be thousands of times greater than a galaxy like the Milky Way.

3C 273 is about 2.5 billion light-years away and is the most distant object visible in a backyard telescope. Recently, Hubble captured its best view of the quasar, revealing previously unseen details in its vicinity.

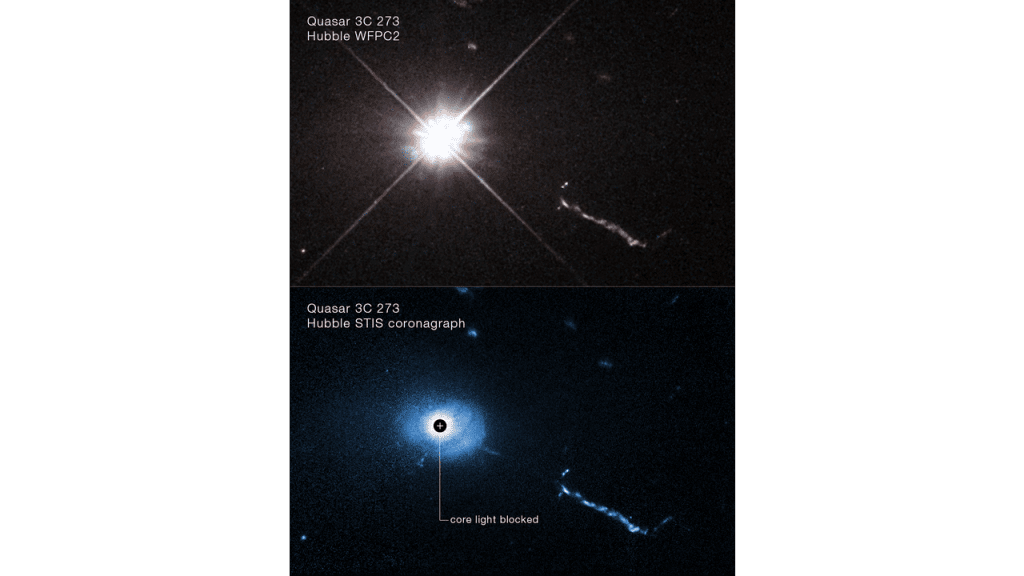

The quasar’s blinding light makes its surroundings difficult to discern. However, astronomers figured out a way to use Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) instrument to make coronagraphic observations of the region. The coronograph allowed astronomers to look eight times closer to the black hole than ever before.

The researchers found a new core jet, a core blob, and other smaller blobs. Their results are in a research letter titled “3C 273 Host Galaxy with Hubble Space Telescope Coronagraphy.” It’s published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, and the lead author is Bin Ren, who also happens to be associated with the California Institute of Technology.

By blocking out the quasar’s blinding glare, Hubble was able to better examine its surroundings. The astronomers found weird filaments, lobes, and a mysterious L-shaped structure. These are all probably the results of the SMBH devouring small galaxies.

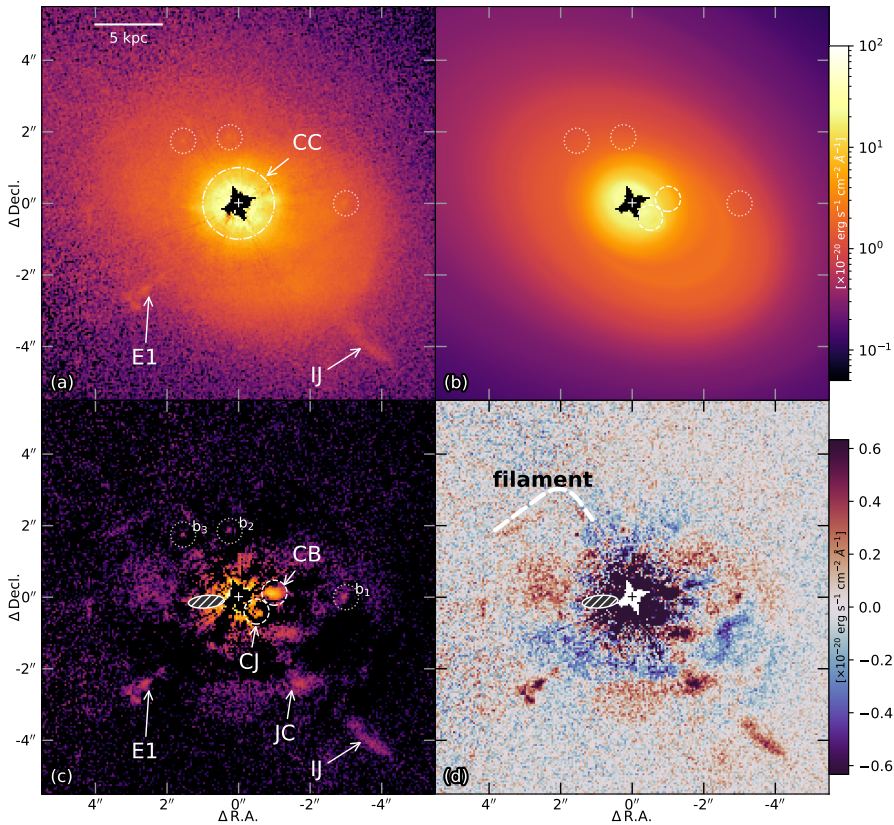

“We have detected a more symmetric core component, CC, for the host galaxy of 3C 273, in addition to confirming the existing large-scale asymmetric components IC and OC that were previously identified in HST/ACS coronagraphy from Martel et al. (2003),” the authors explain in their research letter.

“With the STIS coronagraphic observations, we also identify a core blob (CB) component, as well as other point-sourcelike objects, after removing isophotes from the host galaxy,” the authors continue. “The nature of the newly identified components, as well as the point source-like objects, would require observations from other telescopes for further study.”

There are also filamentary structures to the northeast, east, and west of the galactic nucleus. They extend as far as 10 kiloparsecs (32,600 light-years) from the nucleus. The authors explain that they’re similar to structures observed in other galaxies, where they’re thought to be multiphase gas that’s condensing out of the intergalactic medium. This gas could be fuelling AGN feedback. AGN feedback is a self-regulating process that links the energy released by the AGN to the surrounding gaseous medium.

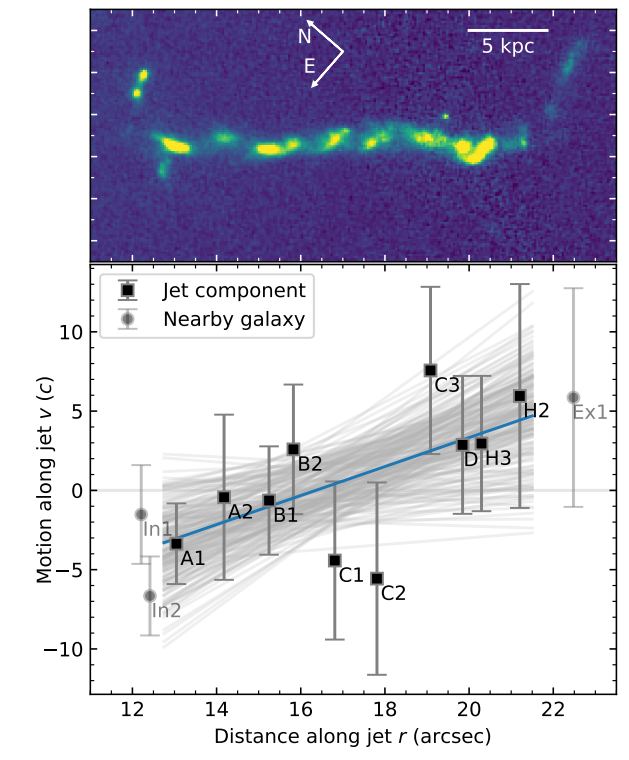

Previous observations of the same quasar 22 years ago allowed the authors to compare images and constrain some properties of the previously observed Inner Jet, which is 300,000 light-years long. “We witness a potential trend that the motion is faster when it is further out,” they write.

This fascinating object begs for more observations to better understand what’s happening. The authors explain that we need methods and telescopes with better inner working angles (IWA) to do that. Both the Hubble and the JWST can do it. “With smaller IWAs for both telescopes, we can both confirm the existence of closest-in components and constrain their physical properties from multi-band imaging. In high-energy observations, we can better characterize such structures,” the authors explain.

“With the fine spatial structures and jet motion, Hubble bridged a gap between the small-scale radio interferometry and large-scale optical imaging observations, and thus we can take an observational step towards a more complete understanding of quasar host morphology. Our previous view was very limited, but Hubble is allowing us to understand the complicated quasar morphology and galactic interactions in detail,” said lead author Ren.

“In the future, looking further at 3C 273 in infrared light with the James Webb Space Telescope might give us more clues,” said Ren.

Read our previous article: Not all stars with black hole companions die gruesome deaths, scientists say