Clyde Tombaugh didn’t set out to discover Pluto when he sent his sketches of the night sky to Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona in 1929. More than anything, he just wanted to get off the farm in Kansas where he spent his days working the earth.

At just 23 years old, Tombaugh sent his drawings, unsolicited, to several institutions and observatories around the United States, hoping someone — anyone — would give him some feedback on what he’d produced.

The response from Lowell Observatory, then, must have been a shock when it hit his mailbox. It was more than a critique of his drawings from professional astronomers. Instead, it was a job offer (from the head of the Observatory, no less), and one that within two years would put Tombaugh in an elite and narrow pantheon of stargazers who could claim what only the ancients could boast: the discovery of a new planet.

The search for Planet X

The search for Pluto did not begin with Clyde Tombaugh, to be fair. That distinction belongs to the visionary astronomer Percival Lowell.

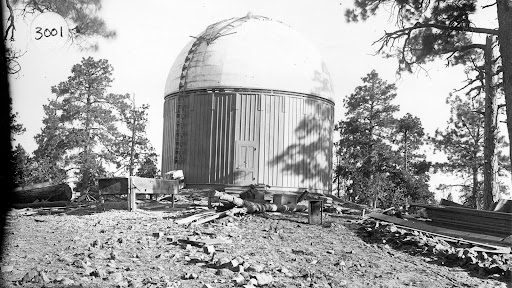

In 1894, Lowell founded Lowell Observatory in the Arizona territory (Arizona wouldn’t become a state until 1912). Originally a scion of an elite Boston family, Lowell became fascinated with the study of Mars and its purported canals. With family wealth to back him, he founded an observatory in the western dark-sky desert of the U.S. and hoped to unlock the mystery of the Red Planet.

He soon became fascinated by another cosmic mystery, however, and one that would be far more consequential. Uranus and Neptune, the most recently discovered planets in the solar system at the time, seemed out of sorts. Their orbits didn’t add up mathematically, and Lowell was convinced there was an undiscovered planet in the far reaches of the solar system that was knocking them off-kilter.

“Lowell wanted to learn more about the planets and started coming under the belief that there might be a ninth planet out there,” Kevin Schindler, Lowell Observatory’s Public Information Officer, told Space.com. “That was based on some irregular motions, or apparent irregular motions, of [Uranus and Neptune].”

He called this hypothetical world “Planet X.”

“In some ways, Pluto’s more of a planet than some of the other established planets, like Mercury.”

Kevin Schindler, Lowell Observatory’s Public Information Officer.

Lowell dedicated years to predicting the location of this elusive planet. He and his team at the observatory came up with calculations for the world’s path and location, but by the time of his death in 1916, the planet (like most other hypothetical worlds), failed to materialize.

With many in the scientific community convinced that there were no more planets to discover, the search for Planet X was abandoned soon after Lowell’s death.

The self-taught astronomer

Clyde Tombaugh‘s journey to planetary discovery is one of the most remarkable in the history of astronomy. Born in 1906 in Illinois and raised on a farm in Burnett, Kansas, Tombaugh had a deep fascination with the night sky. With little formal training, he built his own telescopes and meticulously sketched astronomical observations out in Kansas’s dark-sky country.

“Tombaugh sent some of his drawings off to different places, including Lowell Observatory, and he got this letter back from the director saying, ‘We’re just recommencing the search for a ninth planet, and we need somebody to help with it. It looks like you know what you’re talking about, so why don’t you come work for us?'” Schindler said. “He got a one-way bus ticket, hoping that he wouldn’t have to go back home in a short time, and started working at the observatory.”

Tombaugh arrived in 1929 hoping to prove himself, but his job was painstaking compared to sketching the night sky in Kansas. Using a technique called “blink comparison,” Tombaugh searched through countless, and nearly identical, photographic plates for the elusive planet.

Blink comparison involves looking at photographs of the same portion of the sky on different nights and then rapidly switching between the two images to spot any moving objects. Because far-off stars would be static over successive nights, nearer, moving objects would stand out against the backdrop — but, for an object as distant as Pluto, the motion would be barely perceptible.

It took months of tedious work, flipping back and forth between effectively identical photographic plates, but on February 18, 1930, Tombaugh finally found what he was looking for: a tiny moving speck against the starry background, roughly where Lowell had predicted it would be.

A ninth planet, Pluto, had been discovered.

An ironic discovery

One of the most fascinating aspects of Pluto’s discovery is that it was, in part, a cosmic coincidence.

“Pluto was found really close to where Lowell thought a planet should be, but it’s also a great example of serendipity in science,” Schindler said. “When Lowell was doing his work, there was an estimate of what Uranus’ and Neptune’s masses were, but they weren’t very accurate. Today, we have much more accurate estimates and we know that the irregular motions [that led to the prediction of a Planet X] actually don’t exist. If you know the true value of the masses of Uranus and Neptune, everything’s accounted for.”

In other words, Pluto showing up in Tombaugh’s photos where it did wasn’t the result of careful calculation, but rather a good bit of dumb luck.

“Clyde Tombaugh was looking for a phantom,” Schindler said, “but he found a planet. It was just coincidence that it was right where Lowell thought it should be.”

Pluto’s cultural impact

Lucky find or not, the discovery of Pluto came at a crucial moment in history, particularly for the U.S. By 1930, the Great Depression had left much of the world in economic ruin, and scientific breakthroughs provided a much-needed source of inspiration.

“It had such a cultural impact because we were in the Depression, and there wasn’t much good news in the newspaper,” Schindler said. “It was a good news story in a time of otherwise pretty lousy news.”

Pluto’s discovery was widely celebrated, especially in the U.S. After all, it was the first planet discovered in the new world, and America needed the win in 1930.

“I think because it was discovered by the United States and also discovered in the 20th century with mass media, it has a lot of fascination,” Schindler said. “For decades, Pluto was seen as the ninth planet of the solar system, an underdog among its much larger planetary siblings of the inner planets and the gas giants beyond the asteroid belt.”

However, as scientific understanding evolved, so did Pluto’s classification — though not without controversy.

The reclassification of Pluto

In 2006, Pluto’s planetary status was re-evaluated by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), leading to its reclassification as a “dwarf planet.” The change was based on new criteria for defining planets. According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a planet must:

1. Orbit the sun

2. Be massive to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e., be a spheroid under the force of its own gravity)

3. Clear its orbit of other debris

Pluto fails the third criterion because its orbit overlaps with objects in the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy bodies beyond Neptune. So, a new class of celestial object — the dwarf planet — came into being, with Pluto at its head.

This decision sparked widespread debate, both among the public and among many astronomers.

“There’s this perception that Pluto got dumped,” Schindler said. “So many people took that personally, and we would have guests come to the [Lowell] Observatory saying things like, ‘Are you guys okay?'”

Part of the problem with the reclassification, pioneered by Caltech astronomer Michael Brown and supported by other prominent astronomers like the Hayden Planetarium’s Neil deGrasse Tyson, is that until the reclassification of Pluto as a dwarf planet, no one had really bothered to define what a planet actually was.

“I think [the 2006 reclassification] was a starting point,” Schindler said. “It’s not a bad thing to have a definition of what a planet is, but it’s not really the best definition. It has problems. I think one of the issues [fueling the controversy] is, if scientists are confused about the definition, what’s the rest of the public supposed to do? How are we supposed to understand what a planet is, if scientists can’t even agree on it?”

With Pluto’s “demotion” to dwarf planet status, it’s understandable that the IAU faced criticism from the public for redefining a “planet” in such a way that seemed almost tailored to exclude Pluto, along with bodies like Eris, Ceres and Pallas.

“I don’t want to cast aspersions on the IAU,” Schindler said, “it may be a legitimate definition, but it’s interesting to think about the fact we didn’t have one beforehand. We don’t really have a clear definition of what a planet is; I guess you can say we do now, but it still needs help.”

After all, what does it mean for a planet to “clear its orbit of other debris,” which is the single criterion that Pluto fails? Do Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids qualify as cleared? Earth has plenty of asteroids and other debris in its orbital vicinity, as well. Why do Earth and Jupiter meet this criteria, but Pluto doesn’t?

“At some point, the International Astronomical Union will probably revisit it,” Schindler said, “but I think in some ways, nobody wants to touch it because it’s become sort of an embarrassment. In trying to get to an agreement, not only on what to call a planet but how to decide on what qualifies as a planet, well, the first step was kind of embarrassing. So nobody is in a hurry to revisit it right now.”

Seeing Pluto up close revived the debate

Before Pluto was demoted to dwarf planet status, it was really nothing more than a tiny dot in telescopes; barely a few blurry pixels in an image, and that’s if you were lucky. Even the Hubble Space Telescope, despite all its might, revealed little about the enigmatic object lurking beyond Neptune — but in 2015, NASA’s New Horizons probe gave us our first detailed look at the distant world.

What most people were arguing about in 2006 through 2014 was mostly academic and sentimental. If you grew up learning that Pluto was a planet, chances are you were sticking to that, no matter what the IAU said.

After all, it’s not like anyone had truly seen Pluto before New Horizons performed its 2015 fly-by. And sure enough, afterward, there was definitely a shift — in Pluto’s favor. The images New Horizons sent back were breathtaking, revealing an active, complex planet with mountains, valleys and a now-iconic heart-shaped feature known as Tombaugh Regio.

“New Horizons essentially turned Pluto from a dot to a world where you can see mountains and craters and valleys, all this stuff up close,” Schindler said. “We never saw anything close to that on Pluto before.”

The mission confirmed that Pluto is far from a lifeless rock — it has a dynamic surface, an atmosphere, and potential geological activity, and this only reinforced opinions that Pluto was indeed a planet and had gotten a bad deal from the IAU.

“There’s this perception that Pluto got dumped.”

Kevin Schindler, Lowell Observatory’s Public Information Officer.

“In some ways, Pluto’s more of a planet than some of the other established planets, like Mercury,” Schindler said. “Pluto has several moons orbiting around it and it has an atmosphere. Mercury doesn’t have an atmosphere and it has no moons. Venus doesn’t have a moon, either. Sometimes, if we think traditionally about what a planet is, people will say ‘Well, it’s round, maybe it has some moons, maybe it has an atmosphere.’

“Well, Pluto has them all.”

Celebrating the legacy of discovery

Despite its “demotion,” humanity’s fascination with Pluto hasn’t waned. Every year, the Lowell Observatory hosts the I Heart Pluto Festival to celebrate the discovery and significance of the King of the Kuiper Belt. This event brings together scientists, space enthusiasts and even members of Clyde Tombaugh’s family to honor Pluto’s place in history.

“We started this festival as a way to celebrate Pluto’s discovery and the cultural connections it has,” Schindler said. “It’s about Pluto, but it’s also about the inspiration of space and science.”

This year’s festival theme, “Boldly Go Beyond New Horizons,” brings together figures from science and pop culture, including astronomers, Star Trek actor Leonard Nimoy’s son Adam Nimoy, and others, emphasizing Pluto’s role in both scientific discovery and human imagination.

“I heart Pluto because of its connections,” Schindler said. “I’ve worked at Lowell for almost 30 years, and through that time, I’ve gotten to know so many scientists and others that have a connection to Pluto. I never met Clyde Tombaugh, but I know his children very well, and the scientists at Lowell’s laboratories are good friends that I work with, like Jim Christie, who discovered [Pluto’s moon] Charon in the 1970s.

“For me, it’s definitely the community around Pluto. Yes, I work at the place where it was discovered, but every day I walk past the office where Tombaugh made his discovery, and go past the telescope dome where he huddled himself in the cold and winter to take these pictures. It’s really easy to recreate that day of discovery, and kind of follow his footsteps a little bit, and feel what he was feeling.”

In the end, we all heart Pluto

Pluto’s story is one of perseverance, curiosity and the evolving nature of scientific knowledge. From Percival Lowell’s ambitious search to Clyde Tombaugh’s groundbreaking discovery to the stunning revelations of New Horizons, Pluto continues to captivate us, despite the semantics around its classification.

“I personally think Pluto is a planet and it has nothing to do with the fact that it was discovered where I work,” Schindler said. “Ultimately, Pluto is the prototype of a third zone of the solar system. You have the inner terrestrial planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, then you have the gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. And then, you have this third zone of icy dwarf planets, icy small bodies in the Kuiper Belt — and Pluto’s the big one, the king of those.

“In some ways, what we call it doesn’t matter,” Schindler said. “By naming it a planet or not, it trains us to understand what it is and how it was formed, and that’s the kind of classification that science tries to achieve by seeing similar patterns or differences in the universe.”

Wherever the debate about Pluto’s status goes, one thing is for certain: Pluto’s place in history — and in our hearts — is undeniable. Certainly, the more we learn about it, the more this enigmatic body will inspire us to discover more about the outer frontiers of our stellar neighborhood.

Source link

Read More

Visit Our Site

Read our previous article: Talks turn to rescue as climate changed fire threatens flora