NASA’s Ingenuity Mars helicopter rests on the sandy dunes of the Red Planet’s surface following a crash during its final flight in January. Credit: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory-Caltech/LANL/CNES/CNRS

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and FAA oversee investigations of aircraft accidents in U.S. airspace. But what happens when a crash occurs hundreds of millions of miles away in outer space?

Engineers with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California and uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) manufacturer Aerovironment, a prominent aerospace and defense contractor, are conducting what the space agency on Wednesday said is the first aircraft accident investigation on another world. Personnel are examining the final flight of NASA’s Ingenuity Mars helicopter, which hurtled into the Red Planet’s surface and was retired in January.

Designed to perform five experimental test flights over the course of one month, Ingenuity ultimately flew 72 missions across three years of operation, covering 30 times more ground than planned. Now, NASA knows what caused it to finally meet its end.

A martian helicopter

Strapped beneath NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover, Ingenuity launched to the Red Planet in July 2020 and made its maiden voyage the following April, becoming the first aircraft to fly under its own power on another planet. The “Wright brothers moment” kicked off a campaign that exceeded the space agency’s wildest expectations.

The battery-powered rotorcraft weighs about 4 pounds on Earth but only 1.5 pounds on Mars due to the planet’s thin atmosphere. Flying in those conditions was expected to be challenging — Ingenuity had an intended range of 980 feet and flying altitude of just 15 feet. In April 2022, though, the aircraft set an extraplanetary distance record by covering 2,000 feet at 12 mph. On a different flight, it reached a top altitude of about 79 feet.

Undoubtedly, Ingenuity overperformed. But it eventually came crashing back to Mars.

Flight 72 was intended as a “pop-up” vertical flight to test the rotorcraft’s systems and snap photos of Mars’ Jezero Crater. While it descended from an altitude of about 40 feet, however, NASA lost contact with the Perseverance rover, which had been beaming communications to mission control. When communications were restored, images showed “severe damage” to Ingenuity’s rotor blades.

Without the assistance of on-scene investigators or live footage of the crash, NASA was unable to determine what went wrong. Using what little information the space agency has, though, engineers believe they have pieced together a timeline.

“When running an accident investigation from 100 million miles away, you don’t have any black boxes or eyewitnesses,” said NASA JPL’s Håvard Grip, Ingenuity’s first pilot. “While multiple scenarios are viable with the available data, we have one we believe is most likely: Lack of surface texture gave the navigation system too little information to work with.”

What went wrong

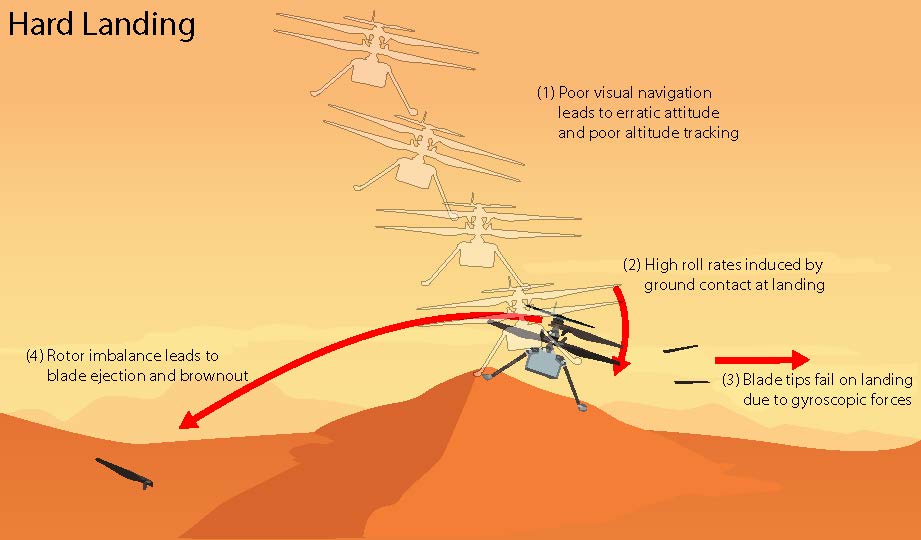

Investigators believe Ingenuity’s visual navigation system — used to help the helicopter track the landscape below it and identify safe landing areas — malfunctioned, causing a “chain of events” that led to the crash.

The navigation system used a downward-facing camera to help Ingenuity fly over flat terrain, and according to NASA, it was sufficient for the helicopter’s five planned missions. But by Flight 72, it had reached a section of the Jezero Crater characterized by “steep, relatively featureless sand ripples.” The navigation system tracked surface features to help Ingenuity adjust its velocity for landing. But according to data analyzed by NASA engineers, it ran out of features to track.

Based on photos of the helicopter after the flight, researchers theorize that it slammed into the sandy slope of the crater at high speed, causing its blades to snap off. The damage created vibrations that snapped off one of the blades at the root, and the resulting power demand on the other blades caused the communications blackout.

Though Ingenuity is grounded, the helicopter continues to beam data from the Martian surface back to NASA about once per week. Avionics data, for example, is helping engineers develop smaller and lighter avionics that could be integrated on vehicles that will return samples from Mars.

Ingenuity alumni are also researching a much larger version of the Mars helicopter called the Mars Chopper. The concept design is about 20 times larger than its predecessor and would be able to carry several pounds of equipment. Its intended range — about 2 miles — would be more than four times farther than Ingenuity’s longest flight.

“Because Ingenuity was designed to be affordable while demanding huge amounts of computer power, we became the first mission to fly commercial off-the-shelf cellphone processors in deep space,” said JPL’s Teddy Tzanetos, project manager for Ingenuity and one of the leads on the Mars Chopper. “We’re now approaching four years of continuous operations, suggesting that not everything needs to be bigger, heavier, and radiation-hardened to work in the harsh Martian environment.”

FAA and NTSB accident investigations are critical for improving the safety of U.S. airspace. In a similar vein, NASA’s otherworldly crash investigation could help future engineers develop the technology the space agency needs to explore for the benefit of humanity.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on Flying.

Read our previous article: Astronomers discover 7 new ‘dark comets,’ but what exactly are they?