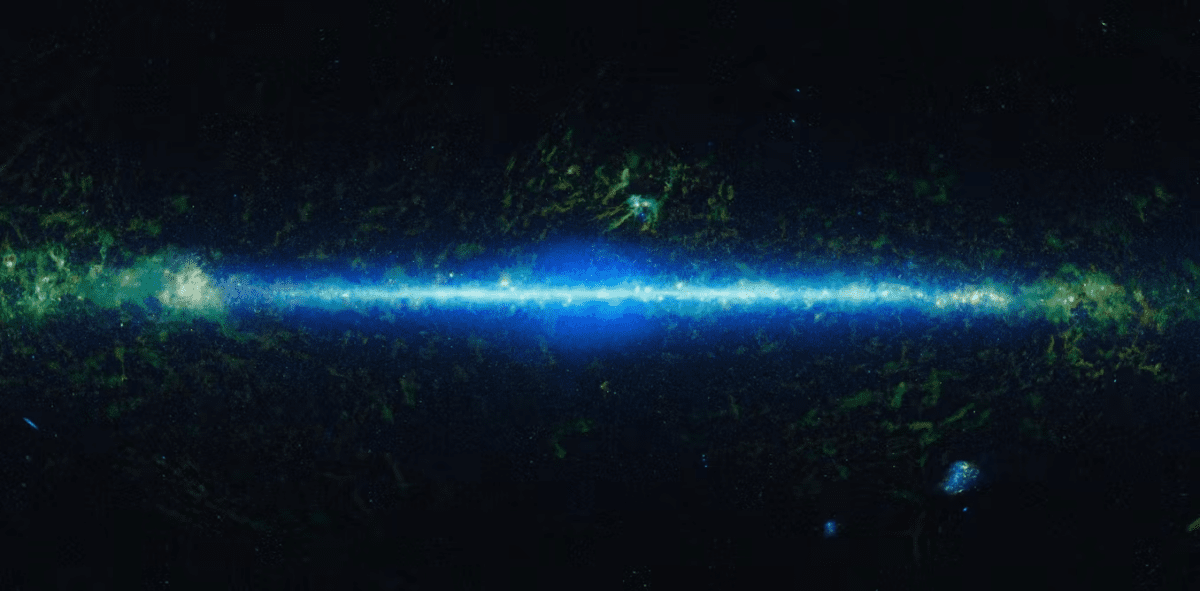

WISE, NEOWISE’s predecessor mission, imaged the entire sky in the mid-infrared range. Credit: NASA/JPL/Caltech/UCLA

The NASA project NEOWISE, which has given astronomers a detailed view of near-Earth objects – some of which could strike the Earth – ended its mission and burned on re-entering the atmosphere after over a decade.

On a clear night, the sky is full of bright objects – from stars, large planets and galaxies to tiny asteroids flying near Earth. These asteroids are commonly known as near-Earth objects, and they come in a wide variety of sizes. Some are tens of kilometers across or larger, while others are only tens of meters or smaller.

On occasion, near-Earth objects smash into Earth at a high speed – roughly 10 miles per second (16 kilometers per second) or faster. That’s about 15 times as fast as a rifle’s muzzle speed. An impact at that speed can easily damage the planet’s surface and anything on it.

Impacts from large near-Earth objects are generally rare over a typical human lifetime. But they’re more frequent on a geological timescale of millions to billions of years. The best example may be a 6-mile-wide (10-kilometer-wide) asteroid that crashed into Earth, killed the dinosaurs and created Chicxulub crater about 65 million years ago.

Smaller impacts are very common on Earth, as there are more small near-Earth objects. An international community effort called planetary defense protects humans from these space intruders by cataloging and monitoring as many near-Earth objects as possible, including those closely approaching Earth. Researchers call the near-Earth objects that could collide with the surface potentially hazardous objects.

NASA began its NEOWISE mission in December 2013. This mission’s primary focus was to use the space telescope from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer to closely detect and characterize near-Earth objects such as asteroids and comets.

NEOWISE contributed to planetary defense efforts with its research to catalog near-Earth objects. Over the past decade, it helped planetary defenders like us and our colleagues study near-Earth objects.

Detecting near-Earth objects

NEOWISE was a game-changing mission, as it revolutionized how to survey near-Earth objects.

The NEOWISE mission continued to use the spacecraft from NASA’s WISE mission, which ran from late 2009 to 2011 and conducted an all-sky infrared survey to detect not only near-Earth objects but also distant objects such as galaxies.

The spacecraft orbited Earth from north to south, passing over the poles, and it was in a Sun-synchronous orbit, where it could see the Sun in the same direction over time. This position allowed it to scan all of the sky efficiently.

The spacecraft could survey astronomical and planetary objects by detecting the signatures they emitted in the mid-infrared range.

Humans’ eyes can sense visible light, which is electromagnetic radiation between 400 and 700 nanometers. When we look at stars in the sky with the naked eye, we see their visible light components.

However, mid-infrared light contains waves between 3 and 30 micrometers and is invisible to human eyes.

When heated, an object stores that heat as thermal energy. Unless the object is thermally insulated, it releases that energy continuously as electromagnetic energy, in the mid-infrared range.

This process, known as thermal emission, happens to near-Earth objects after the Sun heats them up. The smaller an asteroid, the fainter its thermal emission. The NEOWISE spacecraft could sense thermal emissions from near-Earth objects at a high level of sensitivity – meaning it could detect small asteroids.

But asteroids aren’t the only objects that emit heat. The spacecraft’s sensors could pick up heat emissions from other sources too – including the spacecraft itself.

To make sure heat from the spacecraft wasn’t hindering the search, the WISE/NEOWISE spacecraft was designed so that it could actively cool itself using then-state-of-the-art solid hydrogen cryogenic cooling systems.

Operation phases

Since the spacecraft’s equipment needed to be very sensitive to detect faraway objects for WISE, it used solid hydrogen, which is extremely cold, to cool itself down and avoid any noise that could mess with the instruments’ sensitivity. Eventually the coolant ran out, but not until WISE had successfully completed its science goals.

During the cryogenic phase when it was actively cooling itself, the spacecraft operated at a temperature of about -447 degrees Fahrenheit (-266 degrees Celsius), slightly higher than the universe’s temperature, which is about -454 degrees Fahrenheit (-270 degrees Celsius).

The cryogenic phase lasted from 2009 to 2011, until the spacecraft went into hibernation in 2011.

Following the hibernation period, NASA decided to reactivate the WISE spacecraft under the NEOWISE mission, with a more specialized focus on detecting near-Earth objects, which was still feasible even without the cryogenic cooling.

During this reactivation phase, the detectors didn’t need to be quite as sensitive, nor the spacecraft kept as cold as it was during the cryogenic cooling phase, since near-Earth objects are closer than WISE’s faraway targets.

The consequence of losing the active cooling was that two long-wave detectors out of the four on board became so hot that they could no longer function, limiting the craft’s capability.

Nevertheless, NEOWISE used its two operational detectors to continuously monitor both previously and newly detected near-Earth objects in detail.

NEOWISE’s legacy

As of February 2024, NEOWISE had taken more than 1.5 million infrared measurements of about 44,000 different objects in the solar system. These included about 1,600 discoveries of near-Earth objects. NEOWISE also provided detailed size estimates for more than 1,800 near-Earth objects.

Despite the mission’s contributions to science and planetary defense, it was decommissioned in August 2024. The spacecraft eventually started to fall toward Earth’s surface, until it reentered Earth’s atmosphere and burned up on Nov. 1, 2024.

NEOWISE’s contributions to hunting near-Earth objects gave scientists much deeper insights into the asteroids around Earth. It also gave scientists a better idea of what challenges they’ll need to overcome to detect faint objects.

So, did NEOWISE find all the near-Earth objects? The answer is no. Most scientists still believe that there are far more near-Earth objects out there that still need to be identified, particularly smaller ones.

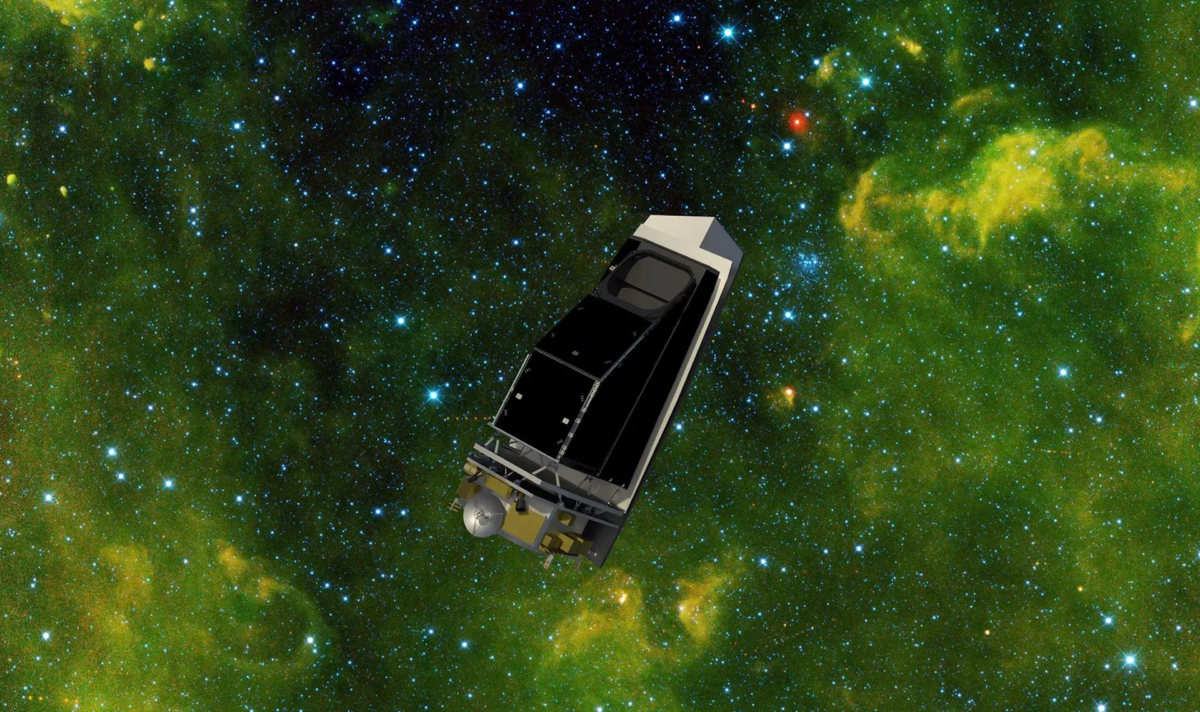

To carry on NEOWISE’s legacy, NASA is planning a mission called NEO Surveyor. NEO Surveyor will be a next-generation space telescope that can study small near-Earth asteroids in more detail, mainly to contribute to NASA’s planetary defense efforts. It will identify hundreds of thousands of near-Earth objects that are as small as about 33 feet (10 meters) across. The spacecraft’s launch is scheduled for 2027.

Toshi Hirabayashi is an Associate Professor of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology. Yaeji Kim is a Postdoctoral Associate in Astronomy, University of Maryland.

Toshi Hirabayashi is a part of several planetary mission teams with NASA, ESA and JAXA through the Georgia Institute of Technology. Yaeji Kim does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read our previous article: MAUVE: An Ultraviolet Astrophysics Probe Mission Concept