Pearl Young, second from left, at the NACA’s Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in 1927. Credit NASA Langley Archives

Thirteen years before any other woman joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics – or the NACA, NASA’s predecessor – in a technical role, a young lab assistant named Pearl Young was making waves in the agency. Her legacy as an outspoken and persistent advocate for herself and her team would pave the way for women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics for decades to come.

My interest in Young’s story is grounded in my own identity as a woman in a STEM field. I find strength in sharing the stories of women who made lasting impacts in STEM. I am the director of the NASA-fundedNorth Dakota Space Grant Consortium, where we aim to foster an open and welcoming environment in STEM. Young’s story is one of persistence through setbacks, advocacy for herself and others, and building a community of support.

Facing challenges from the beginning

Young was a scientist, an educator, a technical editor and a researcher. Born in 1895, she was no stranger to the barriers that women faced at the time.

In the early 20th century, college degrees in STEM fields were considered “less suited for women,” and graduates with these degrees were considered unconventional women. Professors who agreed to mentor women in advanced STEM fields in the 1940s and 1950s were often accused of communism.

In 1956, the National Science Foundation even published an article with the title: “Women are NOT for Engineering.”

Despite society’s sexist standards, Young earned a bachelor’s degree in 1919 with a triple major in physics, mathematics and chemistry, with honors, from the University of North Dakota. She then began her decades-long career in STEM.

Becoming a technical editor

Despite the hostile culture for women, Young successfully navigated multiple technical roles at the NACA. With her varied expertise, she worked in several divisions – physics, instrumentation and aerodynamics – and soon noticed a trend across the agency. Many of the reports her colleagues wrote weren’t well written enough to be useful.

In a 1959 interview, Young spoke of her start at the NACA: “Those were fruitful years. I was interested in good writing and suggested the need for a technical editor. The engineers lacked the time to make readable reports.”

Three years after voicing her suggestion, Young was reassigned to the newly created role of assistant technical editor in the publications section in 1935. After six years in that role, Young earned the title of associate technical editor in 1941.

In 1941, the NACA established the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory, now known as NASA Glenn Research Center, in Cleveland. This new field center needed experienced employees, so two years later, NACA leadership invited Young to lead a new technical editing section there.

It was at the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory that Young published her most notable technical work, the Style Manual for Engineering Authors, in 1943. NASA’s History Office even referred to Young as the architect of the NACA technical reports system.

Young’s style manual allowed the agency to communicate technological progress around the globe. This manual included specific formatting rules for technical writing, which would increase consistency for engineers and researchers reporting their data and experimental results. It was essential for efficient World War II operations and was translated into multiple languages.

But it wasn’t until after this publication that Young finally received the promotion to full technical editor, 11 years after she voiced the need for the role at the agency. She was the first person to hold this role, but she had to start at the assistant level, then move up to associate before receiving the full technical editor designation.

Pearl Young ‘raising hell’

Perhaps the most noteworthy piece of Young’s story is her character. While advocating for herself and her colleagues, Young often had to challenge authority.

She stood up for her editing section when male supervisors wrongfully accused them of making mistakes. She wrote official proposals to properly classify her office in the research division at the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory. She regularly acknowledged the contributions of her entire team for the achievements they shared.

She also secured extra personnel to lessen unbearable workloads and wrote official memorandums to ensure that her colleagues earned rightful promotions. Young often referred to these actions as “raising hell.”

The archival documents I’ve analyzed indicate that Young’s performance at the NACA was exemplary throughout her career. In 1967, she was awarded the University of North Dakota’s prestigious Sioux Award in recognition of her professional achievements and service to the university.

In 1995, and again in 2014, NASA Langley Research Center dedicated a theater in her name. The new theater is located in NASA’s Integrated Engineering Services Building.

In 2015, Young was inducted into the inaugural NASA/NACA Langley Hall of Honor. But throughout her career, not all of her colleagues shared this complimentary view of Young and her work.

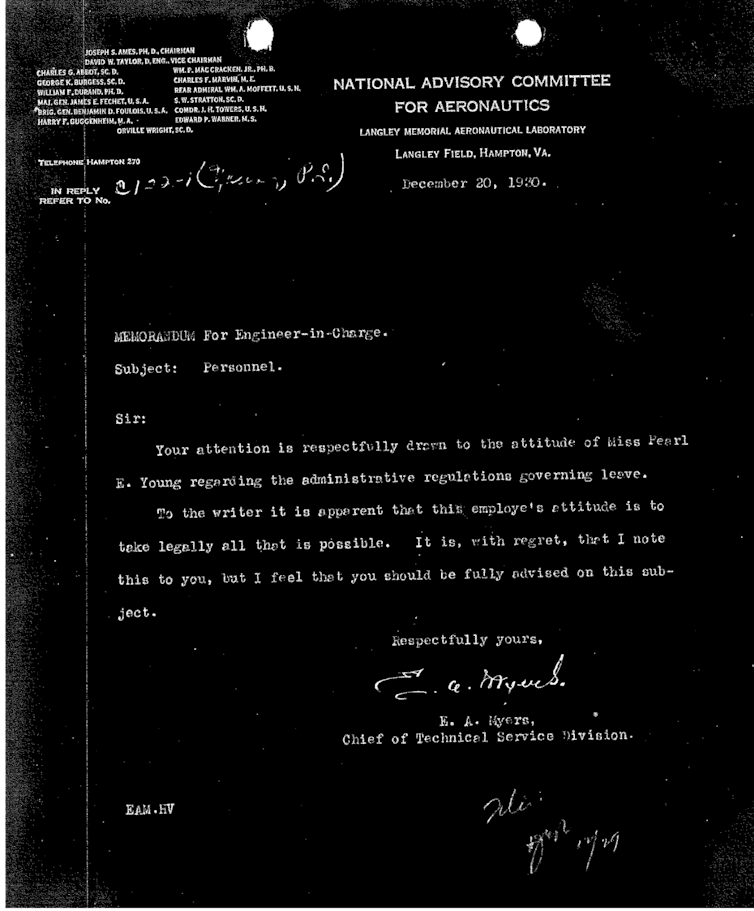

One of Young’s supervisors in 1930 thought it necessary to assess her “attitude” and fitness as an employee in her progress report – and justified his position by typing these additional words into the document himself.

Later that year, Young requested time off – likely for the holiday season – prompting a different supervisor to draft an official memorandum to the engineer in charge, a position akin to today’s NASA center director. He referred to Young’s “attitude” in requesting to use her vacation days.

Women not welcome in STEM

While sexism in STEM has shifted its forms over time, gender-based inequities still exist. Women in STEM frequently confront microaggressions, marginalization and hostile work environments, including unequal pay, lack of recognition and additional service expectations.

Women often lack supportive social networks and encounter other systemic barriers to career advancement, such as not being recognized as an authority figure, or the double standard of being perceived as too aggressive instead of as a leader.

Women of color, women who belong to LGBTQ+ communities and women who have one or more disabilities face even more barriers rooted in these intersectional identities.

One of the ways to combat these inequities is to call attention to systemic barriers by sharing stories of women who persisted in STEM – women like Pearl Young.

Caitlin Milera is a Research Assistant Professor of Aerospace at the University of North Dakota. She receives funding from NASA.

University of North Dakota provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Read our previous article: Meet Endurance, a pioneering NASA moon rover designed to survive the frigid lunar night