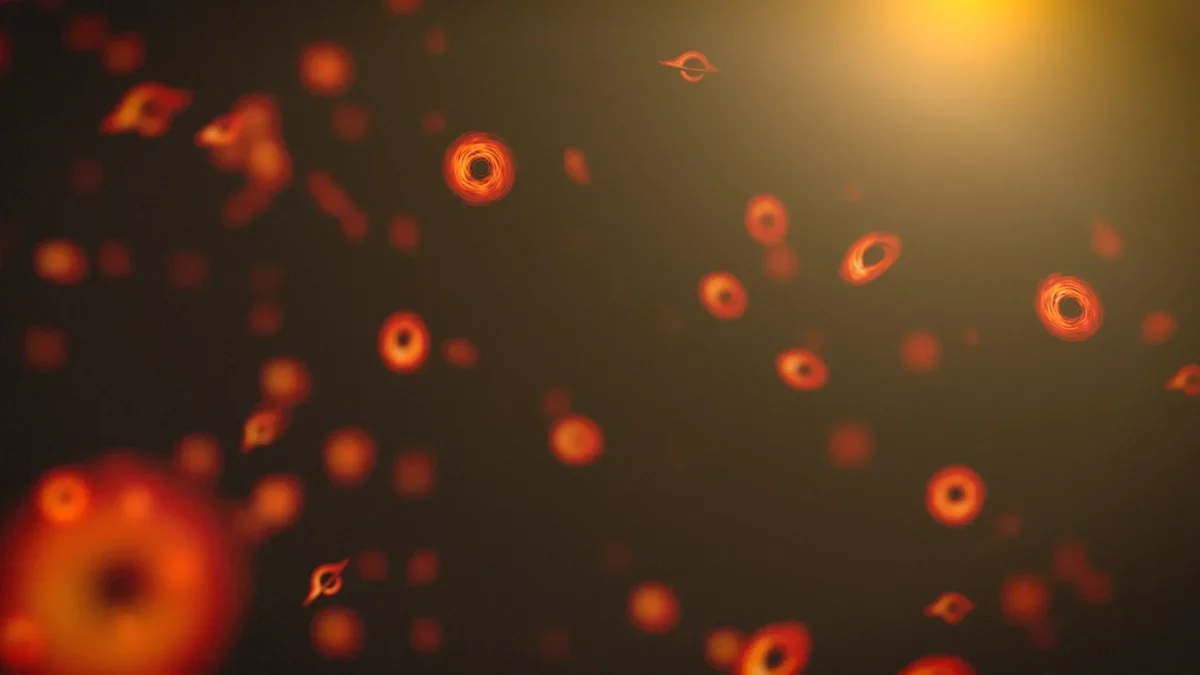

This artist’s concept shows many tiny primordial black holes. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

While black holes are perplexing at any size, some of the most mysterious are hypothetical primordial black holes, those that sprung into existence in the first second after the Big Bang and some of which are featherweights on the black hole scale.

Because black holes collapse matter down to nothing, a black hole with the mass of Earth would have an event horizon no bigger than a dime.

This is what gave two scientists, De-Chang Dai from National Dong Hwa University in Taiwan and Dejan Stojkovic from the University of Buffalo in New York, the idea for their recent paper, published Sept. 20 in Physics of the Dark Universe. In it, they discuss how quickly moving primordial black holes might leave tiny holes in regular matter as they tunnel through, consuming all the material that falls into their itty bitty event horizons.

Specifically, they state that a black hole with a mass of 2.2 x 1019 pounds (1022 grams) would leave a hole 0.1 micron in size, large enough to be seen with a regular optical microscope. The chances of this happening in any given space are astronomically small — but over cosmic time scales, not impossible. In fact, the authors suggest in their paper looking in, “very old rocks, or even glass or other solid structures in very old buildings.”

The odds, they stress, are not good — perhaps vanishingly small. But if people across the world could look for black holes with little to no specialized equipment: what a wonderful chance to spy something incredible.

From the beginning

Primordial black holes are still just a theory. The thinking goes like this: When the universe was still small, in the first second after the Big Bang, all the matter that has ever existed was crammed into a tiny space. Since black holes form from an overdensity of matter, this would reasonably give rise to many black holes of all different sizes, both incredibly tiny and supermassive.

The problem is that we’ve never observed a black hole that can’t be at least mostly explained through other reasons. There are questions of whether the supermassive black holes that reside at the center of galaxies might have started as primordial black holes (they seem to need some kind of boost to have grown so large). But astronomers are sure that at least many black holes form when a massive star ends its life in a catastrophic explosion, and also sure that they can grow larger. There is no understood way to form a black hole smaller than a star in our present universe though. Such an observation — or even indirect evidence of one — would be a big boost for the existence of primordial black holes.

“We have to think outside of the box,” Stojkovic said in a statement, “because what has been done to find primordial black holes previously hasn’t worked.”

The search is important not just for understanding black holes, but also for the Big Bang. Primordial black holes are also one possible explanation for dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up roughly 85 percent of the matter in the universe. Cosmologists can tell the universe is heavier than can be accounted for by stars, dust, and gas, but we cannot see it. And so far it has evaded all attempts at being understood. Black holes, which are massive but invisible, are one possible answer, especially if they could be small and scattered throughout observable space — and even closer to home.

From the inside out

In addition to moving black holes, which would form a tunnel through any material they encounter, the authors also consider what would happen if a primordial black hole were to encounter a celestial object such as a star, planet, or asteroid. Such an encounter might happen during its lifetime, or the black hole might be accreted as part of the overall assembly of the star, planet, or asteroid.

We tend to think of black holes as being voracious, consuming everything in sight. But their reach is limited by gravity, and scales with the black hole’s mass. A black hole as massive as a the Sun would have the Sun’s gravitational reach — and keep in mind that Earth, while subject to the Sun’s gravity, still doesn’t just fall into our central star. Gravity, it turns out, has a shorter range than we tend to think.

So it is quite possible for a small primordial black hole to reside inside, say, a planet. Planets have denser cores than surfaces, so a black hole could feast quickly on that denser material, hollowing out a planet. Large planets would collapse with a hollow core, but asteroids or minor planets made out of strong materials like granite or iron could survive, as long as the primordial black holes weren’t more than ⅒ the radius of Earth.

Again, while such a scenario is unlikely, it’s not impossible over the age of the universe, and astronomers can often infer an object’s mass from how it orbits, making this a straightforward kind of data to collect.

Closer to home

But there are plenty of dense objects all around us. If primordial black holes are commonplace but invisible, we might not even need to look to space.

Tiny black holes could have made or be making even tinier regular holes in substances all around us. The authors recommend older objects, as they have accumulated a greater chance of encountering a black hole. How much greater? Not much. They estimate that the chance of a boulder even one billion years old encountering a black hole is just 0.000001. On the other hand, you could find it simply by walking out to the nearest cliff and taking a peek.

“You have to look at the cost versus the benefit. Does it cost much to do this? No, it doesn’t,” says Stojkovic.

And for anyone worrying if a black hole could be tunneling through them right now, the authors assure readers that humans are much less brittle than a piece of rock, and the black hole would be traveling so fast, you wouldn’t even feel it. “If a projectile is moving through a medium faster than the speed of sound, the medium’s molecular structure doesn’t have time to respond,” Stojkovic says. “Throw a rock through a window; it’s likely going to shatter. Shoot a window with a gun; it’s likely to just leave a hole.”

So, a tiny black hole won’t kill you. But it might have left a hole in your granite countertops. The only way to find out is to go look. You might make history.

Read our previous article: Every upcoming ‘Star Wars’ movie officially announced