- Whale song consists of the sounds and vocalizations that whales make. A new study found these songs follow a specific pattern.

- All human language follows a pattern called Zipf’s law, where the most frequent word is twice as frequent as the second most frequent word and three times as frequent as the third, etc.

- A new study found whale song also follows this law. The researchers believe this is a product of culture and passing along information to the next generation in a way that’s easy to learn.

By Jenny Allen, Griffith University; Ellen Garland, University of St Andrews; Inbal Arnon, Hebrew University of Jerusalem; and Simon Kirby, University of Edinburgh

Whale song follows the same pattern as human language

All known human languages display a surprising pattern: the most frequent word in a language is twice as frequent as the second most frequent, three times as frequent as the third, and so on. This is known as Zipf’s law.

Researchers have hunted for evidence of this pattern in communication among other species. But until now no other examples have been found.

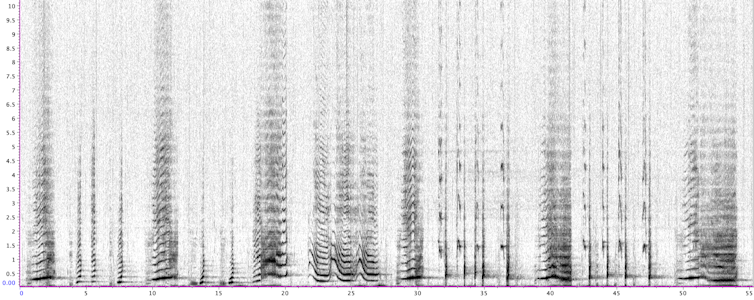

In new research published today in Science, our team of experts in whale song, linguistics and developmental psychology analyzed eight years of song recordings from humpback whales in New Caledonia. Inbal Arnon from the Hebrew University, Ellen Garland from the University of St Andrews and Simon Kirby from the University of Edinburgh led the research. We used techniques inspired by the way human infants learn language to analyze humpback whale song.

We discovered that the same Zipfian pattern universally found across human languages also occurs in whale song. This complex signaling system, like human language, is culturally learned by each individual from others.

The 2025 EarthSky Lunar Calendar is a unique and beautiful poster-sized calendar. Get yours today!

Learning like an infant

When infant humans are learning, they have to somehow discover where words start and end. Speech is continuous and does not come with gaps between words that they can use. So how do they break into language?

Thirty years of research has revealed that they do this by listening for sounds that are surprising in context. Sounds within words are relatively predictable, but between words are relatively unpredictable. We analyzed the whale song data using the same procedure.

Unexpectedly, using this technique revealed in whale song the same statistical properties that are found in all languages. It turns out both human language and whale song have statistically coherent parts.

In other words, they both contain recurring parts where the transitions between elements are more predictable within the part. Moreover, these recurring sub-sequences we detected follow the Zipfian frequency distribution found across all human languages, and not found before in other species.

How do the same statistical properties arise in two evolutionarily distant species that differ from one another in so many ways? We suggest we found these similarities because humans and whales share a learning mechanism: culture.

Listen to whale song

Operation Cetaces916 KB (download)

Audio via Operation Cetaces.

A cultural origin

Our findings raise an exciting question: Why would such different systems in such incredibly distant species have common structures? We suggest the reason behind this is that both are culturally learned.

Cultural evolution inevitably leads to the emergence of properties that make learning easier. If a system is hard to learn, it will not survive to the next generation of learners.

There is growing evidence from experiments with humans that having statistically coherent parts, and having them follow a Zipfian distribution, makes learning easier. This suggests that learning and transmission play an important role in how these properties emerged in both human language and whale song.

So can we talk to whales now?

Finding parallel structures between whale song and human language may also lead to another question: Can we talk to whales now? The short answer is no, not at all.

Our study does not examine the meaning behind whale song sequences. We have no idea what these segments might mean to the whales, if they mean anything at all.

It might help to think about it like instrumental music, as music also contains similar structures. A melody can be learned, repeated, and spread. But that doesn’t give meaning to the musical notes in the same way that individual words have meaning.

Next up: birdsong

Our work also makes a bold prediction: we should find this Zipfian distribution wherever complex communication is transmitted culturally. Humans and whales are not the only species that do this.

We find what is known as vocal production learning in an unusual range of species across the animal kingdom. Songbirds in particular may provide the best place to look, as many bird species culturally learn their songs. And unlike in whales, we know a lot about precisely how birds learn song.

Equally, we expect not to find these statistical properties in the communication of species that don’t transmit complex communication by learning. This will help to reveal whether cultural evolution is the common driver of these properties between humans and whales.![]()

Jenny Allen, Griffith University; Ellen Garland, University of St Andrews; Inbal Arnon, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Simon Kirby, University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Researchers have found that whale song – the sounds and vocalizations of whales – follows the same statistical properties as human language.

Read more: Whales are the biggest living animals: Lifeform of the week

Source link

Read More

Visit Our Site

Read our previous article: Sharks and rays leap out of the water. But why?